No Jam Today and Other Truths of Trading

My naive idea of being a trader was having three connected laptops, someone screaming on the phone, the aggressive clicking of keys, and someone pulling someone’s collar—chaos, long shots of boardrooms, landlines buzzing, Ryan Gosling explaining debt using Jenga, and throw in every other finance movie cliché. My hedge fund module experience at UCL was nothing like that. Chaotic at times, but not as dramatic as the fast-paced moving shot of Andrew Garfield walking down to crush the Mark’s laptop (who doesn’t love the way Fincher shot it). A lot of it was mundane work—ordinary stuff, as you would call it—but if you asked me to talk about it in retrospect, I wouldn’t call it ordinary—No Jam Today, No Jam Tomorrow.

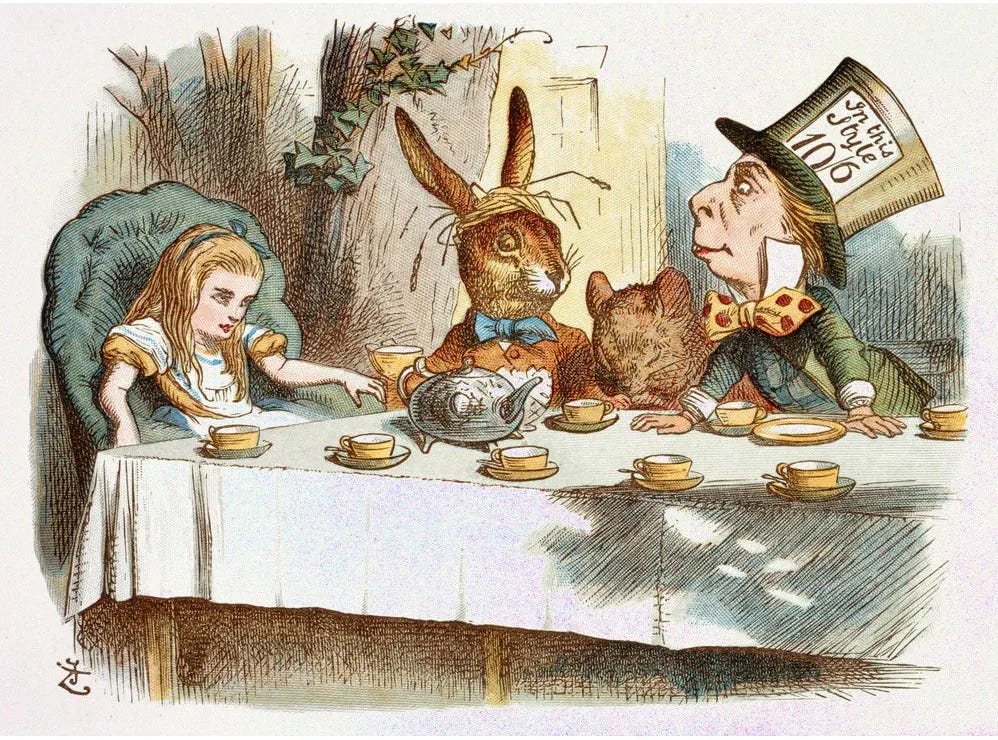

The reason why I am surprised it was a fun experience is because, if I were to break it down, a lot of the individual moments were nothing compared to the fantastical. We didn’t make a million-dollar trade. In fact, our bets were always wrong, and sometimes we forgot to count the right number of zeroes when placing the trade. In Alice in Wonderland, the White Queen offers Alice employment for “Jam yesterday, jam tomorrow, but no jam today!” A lot of life experience—and even my hedge fund module trading—was similar. A lot of the individual moments were mundane, ordinary, the occasional fun ideas and funny company names. As a team, we always hoped tomorrow would be a good day where all of our original ideas (or so we thought) would become the million-dollar trade; some were good, more were bad, but now in hindsight we’ve reframed the past by only remembering all of our good trades. Nostalgia and memory can be tricky, but this simple truism of “No jam today, no jam tomorrow” couldn’t be more profound. We never highlight the drudgery, yet it makes up each brick of the Jenga tower—and yet, on the whole, the sum is greater than its parts.

Alice, Soros, and Inductive Thinking

“She can imagine six impossible things before breakfast.”

— Alice would make a great trader.

Alice ventures into Wonderland, using inductive reasoning to make sense of the new world she is thrown into. She uses trial and error to make sense of what to drink, how to grow tall and what to eat. Brilliant mathematician Lewis Carroll makes a key distinction between impossible and improbable, and this distinction has helped me stay curious and refuse to cling to frameworks. A squared circle is impossible because it is not logically correct, but can pigs grow out of trees? Actually, surprisingly, Yes! Maybe not in our world, because a lot of our reasoning is based on induction—so yes, it hasn't happened yet, but that doesn't mean it can't.

It has helped me to think of financial markets in a similar fashion. Yes, we expect certain models or frameworks to hold true, but it’s based on inductive reasoning, drawing a generalization from the patterns. However, quite a few of them weren’t respected when we had to place trades (talk about luck!). Consumer staples were no longer stable. There was a time when bonds and stocks seemed to move in lockstep, and every time we were surprised at how these changes come about. Improbable, but not impossible!

Unlike us, Alice was never hesitant or surprised in Wonderland. She relied on trial and error to make her way through. Given these traits, I think she would have also invited George Soros to her tea party. He speaks to a similar Theory of Reflexivity, in which he refers to the same underlying notion of curiosity and flexibility of approaches—what a fun tea party to be a part of.

“I did not play the financial markets according to a particular set of rules; I was always more interested in understanding the

changes that occur in the rules of the game.”

— George Soros

Delusions, Biases, and the Soros Rule

After reading all the Daniel Kahneman books and behavioural economic biases, I had an ego that I wouldn't fall prey to them. In trading, it is difficult to disaggregate luck from the right decision-making process. It’s easy to think and perform well when the market is doing well, but what if all hell breaks loose?

“Everyone has a plan until you get punched in the mouth.”

— Mike Tyson

The art of good decision-making is paramount. Paraphrasing Professor George paraphrasing George Soros— “you shouldn’t be able to tell if you had made a million dollars on a trade or lost a million of them”. You need to be able to be objective in your decision-making. Your early success can lead to a warped image of a hot-streak trader.

In poker, where probabilities matter and there’s a personal stake, often finance professionals don’t do well. Maria Konnikova argues that self-assessment and being critical of your thought process is a key great poker player trait. In my trades, initially, we never evaluated why we went right or wrong; we often found ways to blame the market or disillusion ourselves that tomorrow our opinions would be proven correct.

Fast-forward. We didn't get any prediction right.

It’s a dangerous territory— ‘Hopeium’, as Professor George likes to call it. Delusion is punished in poker. Good decision-making requires you to have a well-fleshed-out framework and update Bayesian probabilities if the situation arises. In poker, which I found a lot of nuggets of wisdom relating to trading and life, you are dealt the cards you are dealt. The true test is making objective decisions even when the cards are bad— when the market is volatile.

“Everyone plays well when they’re winning. But can you control yourself and

play well when you’re losing? And not by being too conservative, but trying to still be objective as to what your chances are in the hand. If you can do that, then you’ve conquered the game.”

— The Biggest Bluff: How I Learned to Pay Attention, Take Control and Master the Odds.

Risk, Chess, and Final Reflections

An important aspect we learned while trading and in the module was about Risk. It became something we foregrounded in all of our decisions over a period of time. Risk requires an understanding of probability, of thinking about the continuum of outcomes and preparing for it.

The Chinese symbols for risk capture the beauty of the word—risk combines the symbols which represent danger and opportunity. Calculated, well-thought-out risks are essential, for human cognitive biases are in the shadow—patiently waiting to prey on your reasoning skills to reduce cognitive dissonance and help you settle into grooves. Thinking requires you to challenge your assumptions—just like Alice does as she explores Wonderland. She never assumes the rules of planet Earth work in Wonderland.

Chess players do the same. Nabeel S. Qureshi highlights how this important attribute of actively finding ways to falsify your reasoning is how most chess players think. The way I play chess—or most amateurs—is based on Hopeium, just thinking about the next move, happy that my queen and king are safe—so-called ‘Hope Chess’.

Great chess players spend a large time falsifying their best move, thinking about opportunity, and simultaneously playing out the multiple iterations of danger and opportunity. Alas, like my journey with chess, trading is not a career path for me—but one I am glad I dabbled with.

If you’ve reached the end of this, thanks for sticking around!

Sources

Soros, George. The Alchemy of Finance.

Damodaran, Aswath. Investment Valuation. Referenced for the interpretation of the Chinese symbol for "risk"—a combination of "danger" and "opportunity."

Konnikova, Maria. The Biggest Bluff: How I Learned to Pay Attention, Take Control, and Master the Odds.

Irwin, William & Davis, Richard Brian. Alice in Wonderland and Philosophy: Curiouser and Curiouser.

Namur, George G. Personal Notes from UCL Hedge Fund Module. Personal Class notes drawn from lectures.